A hamster-size dose of sildenafil, more commonly known by its marketing name Viagra, helps the rodent recover more quickly from a six-hour advance in its daily cycle, researchers report.

A hamster-size dose of sildenafil, more commonly known by its marketing name Viagra, helps the rodent recover more quickly from a six-hour advance in its daily cycle, researchers report.

Originally developed for the treatment of high blood pressure and angina, Sildenafil works by interfering with an enzyme that reduces levels of a naturally-occurring compound, cyclic guanine monophosphate (cGMP). In the brain, cGMP has an important function in a signalling pathway that regulates the body’s daily clock.

Biotechnologist Patricia Agostino and colleagues at the Universidad Nacional de Quilmes in Argentina injected hamsters with sildenafil at night, before turning on bright lights six hours earlier than natural sunrise. The team then observed how the hamsters adjusted to the change, by noting how soon they began running in their exercise wheels.

Sildenafil-boosted hamsters recovered from the jet lag up to 50 percent more quickly than unassisted animals. However, the drug only worked when applied before an advance in the light/dark cycle, equivalent to an eastbound flight, rather than the reverse.

The scientists believe that frequent flyers and shift workers could benefit from moderate doses of sildenafil.

The study will be published in the U.S. journal, PNAS, this week.

Tuesday, 22 May 2007

Viagra helps hamsters overcome jet lag

Labels:

Animals,

Health,

News

Posted at

9:56 am

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Monday, 21 May 2007

Do fruit flies have free will?

By Liz Tay

By Liz Tay

In scientific spheres, insects have a reputation similar to that of complex robots that respond predictably to their surroundings. However, a new study has claimed that fruit flies might not be as simple as previously believed, and could actually exhibit free will.

The concept of free will has been a topic of debate, even in relation to humans. Some scientists believe that the purpose of human consciousness is merely to rationalise every decision made by chemical processes in the brain a few milliseconds after the fact. Others believe that once enough is known about the human brain, it will be possible to explain and even predict a person’s behaviour.

"Given this strong claim for humans, it is surprising if prediction should be principally impossible in flies," said Björn Brembs, a biologist from the Free University Berlin and senior author of the fruit fly study. "[But] our work shows that for flies such a prediction will not be possible to the extent claimed."

Together with an international team of researchers, Brembs tethered fruit flies in completely uniform white surroundings and recorded their turning behaviour. In this setup, the flies do not receive any visual cues from the environment, and since they are fixed in space, their turning attempts have no effect.

Without any external stimuli from their surroundings, the scientists expected the flies’ behaviour to resemble random noise, similar to a radio tuned between stations. However, researchers observed the flies behaving non-randomly.

The researchers then tested a plethora of increasingly complex random computer models, all of which failed to adequately model fly behaviour, leading to the conclusion that variability in fruit fly behaviour is not due to simple random events, but is generated spontaneously and non-randomly by the brain. Björn Brembs came up with the idea to study spontaneous behaviour almost 10 years ago in 1998, as part of his work on operant conditioning. However, as he lacked the tools required to conduct experiments, the study was put on hold until late 2004, when discussions with colleague Mark Frye sparked his interest in fruit flies.

Björn Brembs came up with the idea to study spontaneous behaviour almost 10 years ago in 1998, as part of his work on operant conditioning. However, as he lacked the tools required to conduct experiments, the study was put on hold until late 2004, when discussions with colleague Mark Frye sparked his interest in fruit flies.

As a biologist, Brembs is interested in the biological aspects that might enable or prevent the existence of free will. While he believes that absolute freedom is impossible, Brembs questions the extent to which humans and animals are free, and expects this to be where the species differ.

"There is tentative evidence that such a function may be very widespread in the animal kingdom, including humans. If this were indeed the case, we might

have discovered the first evidence for something truly fundamental," he said.

The next step will be to use genetics to localize and understand the brain circuits responsible for the spontaneous behaviour. This step could lead directly to the development of robots with the capacity for spontaneous non-random behaviour and may help combating disorders leading to compromised spontaneous behavioural variability in humans such as depression, schizophrenia or obsessive compulsive disorder.

Labels:

Animals,

Liz,

News

Posted at

12:01 am

|1 comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Saturday, 19 May 2007

King Herod's tomb discovered

By Kathryn Loughman

By Kathryn Loughman

Thousands of years after his death, the King of Judea has returned.

Once ruler of Jerusalem in the first century, King Herod the Great has risen to the forefront of public discussion in the twenty first century.

After many years of archaeological searches, Herod’s tomb was finally found at the site of what is possibly his most outstanding construction, Herodium. The discovery was made when pieces of the desecrated limestone sarcophagus were found by archaeologists.

The dig that led to the discovery was headed by Hebrew University Professor Ehud Netzer, an expert on King Herod who has been working at the site since 1972.

Netzer has said there is no doubt this recent find is the burial site of King Herod, when the historical records and the nature and location of the findings are considered.

Researchers have believed Herodium to be the site of the ancient King’s tomb for many years, based upon the writings of ancient Jewish historian Flavius Josephus. This excavation focused on an area not yet searched.

About 12km south of Jerusalem in the Judean Desert in the West Bank, the recently uncovered tomb site is where it has long been thought and recorded as residing. Mount Herodium is a flattened hilltop between Bethlehem and Masada where Herod constructed a great palace, fortress and monument.

The complex Herod built at Mount Herodium served many purposes, including a residential palace, a sanctuary, a mausoleum and an administrative center. He also built a second palace at the base of the hill, known as ‘Lower Herodium’. The palace included many buildings, pools, gardens, stables, and was the size of a small town.

Renowned for his building projects, in particular the expansion of the second Jewish temple, Mount Moriah, Herodium is Herod’s only project that is also his namesake and is the place he chose to be buried and memorialised.

Herod was a Roman appointed King and therefore faced opposition by Jewish rebels, who are suspected to have destroyed his sarcophagus and stolen his remains during their rebellion against Rome after his death. He reigned from 37-4BCE, at his death.

Herod is also famous in the Christian tradition, which represents him as an evil King who ordered the death of all Jewish baby boys out of fear of a prophetic claim that he would be superseded as King by the birth of baby Jesus.

This find has been described as one the most striking discoveries in Israel in recent years by archaeologists involved in the successful search and has sparked worldwide interest.

Kathryn Loughman is a student and freelance journalist in Sydney, Australia.

Labels:

Ancient Worlds,

Kathryn,

News

Posted at

6:50 pm

|1 comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Wednesday, 16 May 2007

Curbing deforestation could stop climate change - if it exists

By Liz Tay

By Liz Tay

The effect of human activities on climate change is real, according to a new study on tropical deforestation in areas like the Amazon and Indonesia.

Conducted by an international team of researchers from the U.S., U.K., Brazil, France and Australia, the study claims to have confirmed that avoiding deforestation can play a key role in reducing future greenhouse gas concentrations.

Nearly 20 percent of carbon emissions is said to be contributed by deforestation in the tropics. This equates to about 1.5 billion tonnes of carbon each year, adding up to an estimated 130 billion tonnes of carbon by the year 2100.

"[The 2100 projection] is greater than the amount of carbon that would be released by 13 years of global fossil fuel combustion," said CSIRO atmospheric scientist Pep Canadall, who is also a researcher on the Global Carbon Project and on the deforestation study.

"Maintaining forests as carbon sinks will make a significant contribution to stabilising atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations," he said. "The new body of information … also demonstrates the need to avoid higher levels of global warming, which could slow the ability of forests to accumulate carbon." "Climate changes all the time, so if the goal is to keep it constant, or 'sustainable', it is a hopeless task"

"Climate changes all the time, so if the goal is to keep it constant, or 'sustainable', it is a hopeless task"

- Bjarne Andresen

Explaining 'temperature' as a comparative quantity that can only have meaning at a point or for a homogeneous system, Andresen argued that Earth consists of a huge number of components. Adding temperatures together to form a global average would have the same, meaningless effect as calculating the average phone number in a telephone directory, he said.

"The whole idea of global anything is a figment of the imagination," he said. "Effects happen locally and will be different at different spots on Earth; some places will heat up, others cool down."

"Climate changes all the time, so if the goal is to keep it constant, [or] 'sustainable', it is a hopeless task," he said, although stressing that the futility of a constant climate is his personal opinion, and not part of his scientific work.

While he is also of the opinion that humans are ethically obliged not to pollute the environment with poisonous substances like PCB and mercury, Andresen questioned the purpose of using wood, which has sometimes been touted as renewable energy source, instead of coal.

"What is the big difference between the so-called renewable energy source wood as opposed to coal?" he said. "Coal used to be wood as well, so we are actually just burning old wood. In both cases the carbon originally came from the atmosphere and we are returning it there."

Andresen urged climatologists to rethink their methods of analysing climate, as 'equally correct' methods of averaging could each yield wildly different conclusions about the state of the environment.

Emphasising that strong physical arguments are needed to decide on which averaging method to use in describing the climate, Andresen argued that currently approaches to 'global warming' could be employing more of a political, fear-mongering tactic than a scientific approach to the issue.

Atmospheric physicist Michael Box, of the University of New South Wales, defended the averaging methods currently favoured by many climatologists, saying that while 'average temperature' may be a term used loosely by policy makers, 'real' climate scientists use a vast range of inputs as best they can.

"I'm sure all atmospheric physicists know that you can't average temperatures in a strictly formal sense," he said. "However, it is a piece of data that we have going back for a century, so we have something we can compare to."

"We all know that it is temperature gradients which drive the atmosphere - i.e. meteorology," he said. "Nevertheless, an increase in global average temperature is a clear sign that something is going on!"

Labels:

Environment,

Liz,

News

Posted at

7:17 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Thursday, 10 May 2007

Electronic babysitters raise a generation of TV devotees

Just under half of 3-month-old infants are regular viewers of TV, DVDs or videos, a recent survey has found. By the age of two, researchers say, 90 percent of children would have become devotees of the idiot box.

Just under half of 3-month-old infants are regular viewers of TV, DVDs or videos, a recent survey has found. By the age of two, researchers say, 90 percent of children would have become devotees of the idiot box.

Conducted in the U.S. by researchers at the University of Washington (UW) and Seattle Children’s Hospital Research Institute, the study has been touted as the first to investigate the media diet of infants who are too young to speak for themselves.

Through random telephone surveys of more than 1,000 families with children under the age of two in the U.S. states of Minnesota and Washington, researchers found the median age at which infants were regularly exposed to media was 9 months.

Among those who watched TV, DVDs or videos, the average daily viewing time jumped from 60 minutes per day for those children younger than one year to more than 90 minutes a day by two years.

"Early television viewing has exploded in recent years, and is one of the major public health issues facing American children," said Frederick Zimmerman, lead author of the study and a UW professor of health services.

"Exposure to TV takes time away from more developmentally appropriate activities such as a parent or adult caregiver and an infant engaging in free play with dolls, blocks or cars," he said.

A majority of parents cited a belief in the educational properties of media as a reason for permitting their children to watch TV, while others believed viewing to be enjoyable or relaxing for the child. About one fifth of parents surveyed admitted to using electronic media as a babysitter, so they could focus on other chores.

While Zimmerman agreed that appropriate television viewing can be helpful for both children and parents, he warned that excessive viewing before the age of three has been shown to be related to attention problems, aggressive behaviour, and poor cognitive development.

Developmental psychologist Andrew Meltzoff, a co-author of the study and co-director of the UW’s Instutute for Learning and Brain Sciences said: "Most parents seek what's best for their child, and we discovered that many parents believe that they are providing educational and brain development opportunities by exposing their babies to 10 to 20 hours of viewing per week."

"We need more research on both the positive and negative effects of a steady diet of baby TV and DVD viewing," he said, "but parents should feel confident that high-quality social interaction with babies, including reading and talking with them, provides all the stimulation that the growing brain needs."

More information is available from the University of Washington’s press release.

Labels:

News,

Psychology

Posted at

2:09 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Monday, 7 May 2007

Study explains interpersonal barriers in autism

Facial expressions are normally thought to have a significant role in face-to-face communication, giving context and meaning to the words we hear. While most people take the ability to evaluate visual cues for granted, however, a new report has found autistic children lacking in the brain function to discern between a smile and a frown.

Facial expressions are normally thought to have a significant role in face-to-face communication, giving context and meaning to the words we hear. While most people take the ability to evaluate visual cues for granted, however, a new report has found autistic children lacking in the brain function to discern between a smile and a frown.

Researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, studied the brain activity of 16 typically developing children and 16 high-functioning children with autism to determine their responses to faces depicting angry, fearful, happy and neutral expressions.

When children in the typically developing group were shown faces with either a direct or indirect gaze, the researchers found significant differences in activity in a part of the brain called the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), which is known to play a role in evaluating emotions.

In contrast, the autistic children showed no activity in this region of the brain whether they were looking at faces with a direct or an indirect gaze.

"This part of the brain helps us discern the meaning and significance of what another person is thinking," said lead researcher Mari Davies, a graduate student in psychology. "Gaze has a huge impact on our brains because it conveys part of the meaning of that expression to the individual. It cues the individual to what is significant."

The results are said to explain why children diagnosed with autism have varying degrees of impairment in communication skills and social interactions and display restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour.

"They don’t pick up what’s going on — they miss the nuances, the body language and facial expressions and sometimes miss the big picture and instead focus on minor, less socially relevant details," Davies said. "That, in turn, affects interpersonal bonds."

More information is available from the University of California’s press release.

Labels:

News,

Psychology

Posted at

1:50 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Wednesday, 2 May 2007

Alcohol: friend or foe?

It is no secret that Australians like to keep in high spirits. Of course, beer and wine are popular too.

It is no secret that Australians like to keep in high spirits. Of course, beer and wine are popular too.

Recently released statistics on drug use found the average Australian to have consumed 92 litres of beer, 20 litres of wine, and 1 litre of pure alcohol from spirits in 2004 alone. About 35 percent of drinkers were found to consume ‘risky’ levels of alcohol, the abuse of which has been blamed for more than a quarter of all deaths of 15 to 29 year-olds in developed countries.

According to biotechnologists from the University of Granada in Spain, however, melatonin found in red wine could delay the oxidative damage and inflammatory processes typical of old age. Though laboratory tests with mice, scientists speculate that daily melatonin intake in humans from the age of 30 or 40 could delay illnesses related to aging, thus promoting longevity.

While exploring ways to keep berries fresh during storage, researchers at the Kasetsart University in Thailand have discovered health benefits in treating the fruit with alcohol. Besides helping berries resist decay, alcohol was found to increase antioxidant capacity within strawberries, and could also increasing their ability to prevent diseases ranging from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders.

Strawberry daiquiri, anyone?

Labels:

Health,

Mashups

Posted at

2:51 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Monday, 30 April 2007

Solid light gains weight in future technology

The properties of light in a solid-like state as formed the basis for a new theory said to have potentials in future electronics.

The properties of light in a solid-like state as formed the basis for a new theory said to have potentials in future electronics.

By studying light with tools more commonly used to study matter, researchers have developed a theory that shows that the interactions of photons can be similar that of a solid.

"Solid light photons repel each other as electrons do. This means we can control photons, opening the door to new kinds of faster computers," said Andrew Greentree, a physicist at the University of Melbourne.

"Many real-world problems in quantum physics are too hard to solve with today’s computers. Our discovery shows how to replicate these hard problems in a system we can control and measure," he said.

While photons of light do not normally interact with each other as strongly as the electrons currently used in electronics, the researchers have shown theoretically how to engineer a 'phase transition' in photons, leading them to change their state so that they do interact with each other.

Greentree said the solid light phase transition effect ties together two very different areas of physics, optics and condensed matter 'to create a whole new way of thinking'.

More information is available from the University of Melbourne’s press release.

Labels:

News,

Technology

Posted at

2:05 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Thursday, 26 April 2007

Astronomers find first habitable Earth-like planet

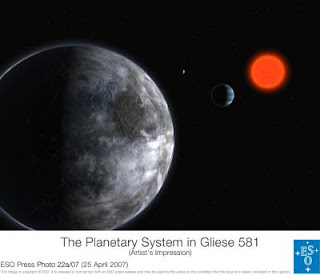

Astronomers have discovered the most Earth-like planet outside our Solar System to date, an exoplanet with a radius only 50 percent larger than the Earth and capable of having liquid water.

Astronomers have discovered the most Earth-like planet outside our Solar System to date, an exoplanet with a radius only 50 percent larger than the Earth and capable of having liquid water.

This exoplanet - as astronomers call planets around a star other than the Sun – is the smallest ever found up to now and it completes a full orbit in 13 days. It is about five times the mass of the Earth that orbits a red dwarf at a distance about 14 times less than the Earth is from the Sun.

However, as the red dwarf, Gliese 581, is smaller and colder than the Sun – and thus less luminous – scientists speculate that the planet nevertheless lies in the habitable zone, the region around a star where water could be liquid!

"We have estimated that the mean temperature of this super-Earth lies between 0 and 40 degrees Celsius, and water would thus be liquid," explains Stéphane Udry, from the Geneva Observatory (Switzerland) and lead-author of the paper reporting the result.

"Moreover, its radius should be only 1.5 times the Earth’s radius, and models predict that the planet should be either rocky – like our Earth – or covered with oceans," he adds.

Artist's impression of the system of three planets surrounding the red dwarf Gliese 581 - ESO

"Liquid water is critical to life as we know it," avows Xavier Delfosse, a member of the team from Grenoble University (France). "Because of its temperature and relative proximity, this planet will most probably be a very important target of the future space missions dedicated to the search for extra-terrestrial life. On the treasure map of the Universe, one would be tempted to mark this planet with an X."

The host star, Gliese 581, is among the 100 closest stars to us, located only 20.5 light-years away in the constellation Libra. It has a mass of only one third the mass of the Sun. Such red dwarfs are intrinsically at least 50 times fainter than the Sun and are the most common stars in our Galaxy: among the 100 closest stars to the Sun, 80 belong to this class.

"Red dwarfs are ideal targets for the search for low-mass planets where water could be liquid. Because such dwarfs emit less light, the habitable zone is much closer to them than it is around the Sun," emphasizes Xavier Bonfils, a co-worker from Lisbon University. Planets lying in this zone are then more easily detected with the radial-velocity method, the most successful in detecting exoplanets.

More information is available from the European Space Observatory’s press release.

Labels:

Astronomy,

News

Posted at

3:28 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Tuesday, 24 April 2007

Carbon fibre heralds in cars of the future

Cars and aeroplanes in the near future could be lighter, stronger, safer, and more energy efficient with the use of carbon fibre materials currently in development by material scientists in Victoria.

Cars and aeroplanes in the near future could be lighter, stronger, safer, and more energy efficient with the use of carbon fibre materials currently in development by material scientists in Victoria.

The development could see a new generation of cars and aeroplanes with lower energy consumption and improved safety, scientists say.

“There are enormous benefits in converting steel and aluminium parts in cars to lighter materials, especially in fuel savings,” said lead researcher Bronwyn Fox of Deakin University's Centre for Material and Fibre Innovation.

“Using carbon fibre composites produces lighter cars. Lighter cars are more fuel-efficient. Carbon fibre has a higher stiffness to weight ratio than steel, but it also absorbs more energy per kilogram, with the potential to make cars lighter and safer," he said.

More information is available from Deakin University's press release.

Labels:

News,

Technology

Posted at

8:22 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Friday, 20 April 2007

Shock, awe, and science journalism

Airing the views of climate change sceptics in the media only serves to keep controversy boiling, scientists have told the World Conference of Science Journalists in Melbourne, Australia.

Airing the views of climate change sceptics in the media only serves to keep controversy boiling, scientists have told the World Conference of Science Journalists in Melbourne, Australia.

Kevin Hennessy, Australian scientist and lead author of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group II report, said this week that media attention on "the view of a handful of climate change sceptics" amplifies their opinions and "implies that there is little agreement about the basic facts of global warming".

Speaking in a session about climate change reporting, he said editors and journalists have a duty to ensure that facts are presented in context. Balanced reporting, he said, "perpetuates the public's perception that scientists are in disarray, which is misleading in the case of climate change".

Geoff Love, vice chair of the IPCC Working Group II, said that the IPCC assessment reports ― from 1990, 1995, 2001 and February 2007 ― are strong evidence of "the coming together of the scientific community" and that emphasis on the sceptic view does not help public understanding of climate change.

Media coverage has not always reflected the consensus of the majority of the scientific community, said Ian Lowe, president of the Australian Conservation Foundation. "That only makes the public and political discussion more difficult," he said.

More information is available from the original article at SciDev.net.

Labels:

Environment,

News

Posted at

5:53 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Thursday, 19 April 2007

Hydrogen combustion engine aims to reduce greenhouse emissions

Researchers in Melbourne are developing a low-cost hydrogen combustion engine and fuel tank, in efforts to help make hydrogen a real alternative to carbon dioxide-emitting fuels.

Researchers in Melbourne are developing a low-cost hydrogen combustion engine and fuel tank, in efforts to help make hydrogen a real alternative to carbon dioxide-emitting fuels.

The project is being conducted by engineers at the University of Melbourne in conjunction with industry collaborators, Ford Australia and Haskel Australia.

"Ultimately this will open up a whole new market for not previously developed low-cost fuel efficient hydrogen-powered vehicles," said project leader Michael Brear, of the University’s school of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering.

Brear said a goal of the $3 million project, which is supported in part by State Government funding, is to build a Victorian-manufactured engine that should achieve the world’s highest efficiency for a hydrogen-fuelled internal combustion engine.

He said hydrogen is seen as a transport fuel of the future because its reaction with air does not produce carbon dioxide, a major cause of climate change.

Many proposed hydrogen fuelled vehicles, however, are viewed as excessively expensive and impractical due to limited compression and storage capacity.

"Existing storage methods such as pressurisation of hydrogen to 350-700 atmospheres, are excessively large, very heavy or unaffordable and do not show a clear path to meeting automotive requirements," he said. "We will investigate a novel approach to high density storage of hydrogen at pressures that allow use of conventional storage equipment."

More information is available from the University of Melbourne’s press release.

Labels:

News,

Technology

Posted at

5:26 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Wednesday, 18 April 2007

Sleep organises memories

We have usually quite strong memories of past events like an exciting holiday or a jolly birthday party. However it is not clear how the brain keeps track of the temporal sequence in such memories: did Paul spill a glass of wine before or after Mary left the party?

We have usually quite strong memories of past events like an exciting holiday or a jolly birthday party. However it is not clear how the brain keeps track of the temporal sequence in such memories: did Paul spill a glass of wine before or after Mary left the party?

Previous findings from a research group headed by Jan Born at the University of Lübeck have confirmed the widely held view that long-term memories are formed particularly during sleep, and that this process relies on the brain replaying recently encoded experiences during the night. The same research group now provides evidence that sleep not only strengthens the content of a memory but also the particular order in which they were experienced, probably by a replay of the experiences in "forward" direction.

Students were asked to learn triplets of words presented one after the other. Afterwards they slept, whereas in a control condition no sleep was allowed. Later, recall was tested by presenting one word and asking which one came before and which one came after during learning. Sleep was found to enhance word recall, but only when the students were asked to reproduce the learned words in forward direction.

This finding shows that sleep associated consolidation of memories enforces the temporal structure of the memorized episode that otherwise might be blurred to a timeless puzzle of experiences.

Findings of the study are reported in the international online journal of the Public Library of Science, PLoS ONE

Labels:

News,

Psychology

Posted at

11:46 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Tuesday, 17 April 2007

Chill out, live longer

A psychological study has linked neuroticism and mortality, suggesting that mellowing with age could help people live longer.

A psychological study has linked neuroticism and mortality, suggesting that mellowing with age could help people live longer.

In the study, researchers tracked the change in neuroticism levels of 1,663 aging men over a 12-year period.

A neurotic personality was defined as a person with the tendency to worry, feel excessive amounts of anxiety or depression and to react to stressful life events more negatively than people with low levels of the trait. Neuroticism levels were measured using a standardized personality test.

Using the data gathered in the first analysis, researchers calculated the men's mortality risk over an 18-year period using the average levels and rates of change.

By the end of the study, half of those men classified as highly neurotic with increasing levels of neuroticism had died while those whose levels decreased or were classified as less neurotic had between a 75 percent and 85 percent survival rate.

"We found that neurotic men whose levels dropped over time had a better chance at living longer," said Dan Mroczek, an associate professor of child development and family studies at Purdue University, who conducted the study. "They seemed to recover from any damage high levels of the trait may have caused. On the flip side, neurotic men whose neuroticism increased over time died much sooner than their peers."

The study will be published in the print edition of the U.S. journal Psychological Science in late May. More information is available from Purdue University’s press release.

Labels:

Health,

News,

Psychology

Posted at

11:34 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Monday, 16 April 2007

Cannabis could provide relief to stroke patients

Some mechanisms in the brain targeted by cannabis have been found to have potentials in countering brain cell damage after a stroke.

Some mechanisms in the brain targeted by cannabis have been found to have potentials in countering brain cell damage after a stroke.

New research by scientists at the University of Otago in New Zealand has shown that the cannabinoid CB2 receptor appears in the rat brain following a stroke. The findings have been touted as a world-first, and were published recently in the international journal Neuroscience Letters.

The CB2 receptor is a protein produced in response to stroke as part of the body's immune response system. This response causes the inflammation that leads to damage in the area of the brain around where the stroke has occurred, according to John Ashton, a medical researcher at the University’s Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology.

"If the inflammation can be stopped or reduced then it offers the hope of reducing the extent of the damage caused by stroke - and CB2 offers a potential target for such a drug,” he said.

Ashton explained that the active ingredient of cannabis, THC, targets both the CB2 and the related CB1 receptors. But while THC has been known to have some positive effects for pain management, its use is currently severely limited because of how it triggers the psychoactive CB1 receptors in the brain.

"The aim would be to develop a drug that targets the CB2 receptor without affecting CB1," Ashton said, suggesting a pharmaceutical approach similar to that that has already been taken to develop codeine from heroin.

"Heroin and codeine share common targets, but by designing codeine in such a way that it eliminated the psychoactive side-effects seen with heroin, a therapeutically useful drug was developed. There is the potential to do the same with cannabinoids," he said.

Drugs targeting CB2 could also have potential therapeutic use in other conditions involving inflammatory damage to the brain, such as Huntington's Disease and Alzheimer's Disease. There may also be scope to use them in pain management.

More information is available from the University of Otago’s press release.

Labels:

Health,

News

Posted at

3:22 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Friday, 13 April 2007

Harvard study uncovers soccer referee bias

By Reidar von Hirsch

By Reidar von Hirsch

Fans of football will be relieved by the findings of a new report soon to be released at Harvard University - all those hours in the stands cheering at the team and shouting at the referee have not been in vain.

A study by Harvard University professor, Ryan Boyko, has found evidence that supports a long-held assertion by fans of the game - that playing at home gives the extra push to ensure a victory.

Boyko himself is a life-long footballer on youth and amateur level, now turned football referee in the US College divisions. Feeling the pressure from the crowd he decided, together with his brother Mark Boyko, to look into whether this could be statistically proven.

"We decided to look into what research had been done before and found a number of studies suggesting that crowd noise can bias referees toward the home team but nothing that actually demonstrated it had real effects on the game," he said.

"The obvious difficulty being that it's difficult to show that it is the referees being biased as opposed to the away players playing dirtier or worse, but our idea was that if referee psychology was the culprit different referees would respond significantly differently to crowd noise and this is exactly what we found."

A look at the final table for the A-League last season shows that winners Melbourne Victory actually won more away games than home games - according to this study a damning verdict on their fans, or perhaps the fans of their away game opponents. The Victory won six home games and eight away games in the 2006-7 season.

But perhaps more importantly, the study also shows something far more worrying, that also the referees are prone to influence from the home crowd. The team playing at home is more likely to get a penalty kick than the opposing team.

"The most interesting revelation unrelated to referee home bias that we found was that how many cards a team received in a match seem to be most determined by how many cards opponents of the other team generally get, not on any characteristic of the particular team in question," Boyko said.

"Thus it seems that certain teams are better at drawing fouls from the other team and that this effect is more important even than a team's propensity to get in trouble themselves."

Another phenomenon in big league football that also can be explained by this study is a claim by fans of smaller clubs - that referees more often take the side of the bigger team. This might be true simply because bigger teams have bigger crowds. Crunching the numbers, Boyko's studies found that ten percent more goals were scored by a home team per 10,000 spectators.

"Teams that consistently draw more spectators do seem to have a bigger home advantage and our study was unable to definitively answer whether this was due to merely having more spectators or some other variable correlated with number of spectators, such as team or player reputations."

On a stadium like Old Trafford, where famous Manchester United just this week played a stunning 7-1 win against Italian number-twos Roma, this means almost 75,000 spectators, or an output of no less than 0.75 goals per match.

In the Asian Champions League and the European Champions League, the home advantage is taken into account in the tournament regulations with the so-called away-goal rule. However, this does not officially relate to the home-bias refereeing revealed in Boyko's study, but to the pressure a team feels from playing on hostile grounds. A team in these tournaments that scores more away goals than its opponent in a knock-out game proceeds if the overall standing is a tie.

When it comes to doing something about the home-bias, Boyko says referee training and assessment could be effective. Any kind of video refereeing, meaning the game is stopped to make sure what really has happened is one of the most controversial debates in football today - some say it would make it more fair, others claim it would slow it down and take away the magic of the game. Boyko agrees that it probably wouldn't be worth it to implement full video refereeing, as is common in other forms of football.

"One relatively simple thing that could be done is installing goal line cameras such that a judge in a booth can review perhaps the most important decision of all - whether a goal has been scored or not. In this instance it could be done in a matter of seconds and probably wouldn't break up the flow of the game much. In other cases it might not be worth trying to move decisions away from the referee on the field as it might slow the game down too much and take away from the essence of the sport."

"These are questions that should be thought about intelligently and addressed by the governing bodies of professional and international soccer in light of the evidence from our study and others' studies," he said.

Reidar von Hirsch is a soccer enthusiast and freelance journalist in Sydney, Australia.

Labels:

News,

Psychology,

Reidar

Posted at

2:06 pm

|1 comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Thursday, 12 April 2007

Alien plants might not necessarily be green

Green, yellow or even red-dominant plants may live on extra-solar planets, speculate NASA scientists who believe they have found a way to predict the colour of plants on planets in other solar systems.

Green, yellow or even red-dominant plants may live on extra-solar planets, speculate NASA scientists who believe they have found a way to predict the colour of plants on planets in other solar systems.

The scientists, whose reports appear in the March issue of U.S. journal, Astrobiology, studied light absorbed and reflected by organisms on Earth, and determined that if astronomers were to look at the light given off by planets circling distant stars, they might predict that some planets have mostly non-green plants.

Besides improving our understanding of life on Earth, the findings can potentially improve current methods of searching for life elsewhere in the universe, scientists say.

"We can identify the strongest candidate wavelengths of light for the dominant colour of photosynthesis on another planet," said Nancy Kiang, lead author of the study and a biometeorologist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, New York.

Kiang and her colleagues calculated what the stellar light would look like at the surface of Earth-like planets whose atmospheric chemistry is consistent with the different types of stars they orbit. By looking at the changes in that light through different atmospheres, researchers identified colours that would be most favourable on other planets for photosynthesis, which is a process by which plants use energy from sunlight to produce sugar.

It has long been known that the chlorophyll in most plants on Earth absorbs blue and red light and less green light, so chlorophyll appears green. According to scientists, the Sun has a specific distribution of colours of light, emitting more of some colours than others. Gases in Earth's air also filter sunlight, absorbing different colours. As a result, more red light particles reach Earth's surface than blue or green light particles, so plants use red light for photosynthesis.

But not all stars have the same distribution of light colours as our Sun. Study scientists say they now realize that photosynthesis on extrasolar planets will not necessarily look the same as on Earth. Scientists expect each planet to have different dominant colours for photosynthesis, based on the planet’s atmosphere where the most light reaches the planet’s surface. The dominant photosynthesis might even be in the infrared.

"It makes one appreciate how life on Earth is so intimately adapted to the special qualities of our home planet and Sun," Kiang said.

More information is available from NASA's press release.

Labels:

Astronomy,

News

Posted at

9:11 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Wednesday, 11 April 2007

Power advancements in tiny electronics

Consumer electronics seem to be getting smaller by the day, with size becoming an increasingly poor indication of gadgets' power requirements and capabilities.

Consumer electronics seem to be getting smaller by the day, with size becoming an increasingly poor indication of gadgets' power requirements and capabilities.

Computer scientists and engineers at the Virginia Commonwealth University are taking a new spin on data storage with the development of spin-based electronics, dubbed ‘spintronics’ for short. The technology is said to be able to supersede the limitations of Moore’s Law due to the lower energy requirements of storing information in the spin of an electron, instead of in its charge.

Electrochemists at the St Louis University are taking another approach to the issue of power. A research team is currently developing fuel cell technology that uses enzymes to extract energy from virtually any sugar source. This essentially means that any sugar solution, from soft drinks to plant sap, may soon be used to power portable electronics like cellular phones, laptops, and sensors.

Meanwhile, researchers at the Delft University of Technology are looking to make batteries smaller in order to improve their operation. A team of applied scientists are developing nanoscale batteries that are expected to deliver more usage between charges, and shorter charge/discharge times, to mobile consumers and users of electric vehicles within the next five years.

Labels:

Mashups,

Technology

Posted at

7:15 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Tuesday, 10 April 2007

Maize farming found to predate Mayans by a millenium

New evidence has surfaced to suggest that ancient farmers in Mexico were cultivating an early form of maize, the forerunner of modern corn, about 7,300 years ago - 1,200 years earlier than scholars previously thought.

New evidence has surfaced to suggest that ancient farmers in Mexico were cultivating an early form of maize, the forerunner of modern corn, about 7,300 years ago - 1,200 years earlier than scholars previously thought.

The findings expand on previous research that demonstrate the rapid spread of maize from southwest Mexico to the southeast and other tropical areas in the Americas, including Panama and South America.

Through an analysis of sediments in the Gulf Coast of Tabasco, Mexico, Florida State University anthropologist Mary Pohl concluded that people were planting crops in the ‘New World’ of the Americas around 5,300 B.C.

"This research expands our knowledge on the transition to agriculture in Mesoamerica," Pohl said. "These are significant new findings that fill out knowledge of the patterns of early farming.”

The shift from foraging to the cultivation of food was a significant change in lifestyle for these ancient people and laid the foundation for the later development of complex society and the rise of the Olmec civilization, Pohl said. The Olmecs predated the better known Mayans by about 1,000 years.

During her field work in Tabasco seven years ago, Pohl found traces of pollen from primitive maize and evidence of forest clearing dating to about 5,100 B.C.

Pohl's study analysed phytoliths - the silica structure of a plant - from traces of maize pollen that previous studies have found to date back to about 5,100 B.C. Her analysis puts the date of the introduction of maize in southeastern Mexico 200 years earlier than her pollen data indicated.

It also shows that maize was present at least a couple hundred years before the major onset of forest clearing. Traces of charcoal found in the soil in 2000 indicated the ancient farmers used fire to clear the fields on beach ridges to grow the crops.

"This significant environmental impact of maize cultivation was surprisingly early," she said. "Scientists are still considering the impact of tropical agriculture and forest clearing, now in connection with global warming."

The discovery of cultivated maize in Tabasco, a tropical lowland area of Mexico, challenges previously held ideas that Mesoamerican farming originated in the semi-arid highlands of Mexico and shows an early exchange of food plants.

A report on the results of the study will be published in the April 9-13 edition of the U.S. journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. More information is available from the Florida State University’s press release.

Labels:

Ancient Worlds,

News

Posted at

10:18 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Thursday, 5 April 2007

Brain’s breaking mechanism revealed

As wise as the counsel to ‘finish what you've started’ may be, it is also sometimes critically important to do just the opposite - stop. And according to a recent cognitive study, the ability to stop quickly, to either keep from gunning the gas when a pedestrian steps into your path or to bite your tongue mid-sentence when the subject of gossip suddenly comes into view, may depend on a few ‘cables’ in the brain.

As wise as the counsel to ‘finish what you've started’ may be, it is also sometimes critically important to do just the opposite - stop. And according to a recent cognitive study, the ability to stop quickly, to either keep from gunning the gas when a pedestrian steps into your path or to bite your tongue mid-sentence when the subject of gossip suddenly comes into view, may depend on a few ‘cables’ in the brain.

Researchers led by cognitive neuroscientist Adam Aron, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, San Diego, have found white matter tracts - bundles of neurons, or 'cables', forming direct, high-speed connections, between distant regions of the brain - that appear to play a significant role in the rapid control of behaviour.

The study is the first to identify these white matter tracts in humans, confirming similar findings in monkeys, and the first to relate them to the brain's activity while people voluntarily control their movements.

"Our results provide important information about the correspondence between the anatomy and the activity of control circuits in the brain," Aron said. "We've known for some time about key brain areas involved in controlling behaviour and now we're learning how they're connected and how it is that the information can get from one place to the other really fast."

"The findings could be useful not only for understanding movement control," Aron said, "but also 'self-control' and how control functions are affected in a range of neuropsychiatric conditions such as addiction, Tourette's syndrome, stuttering and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder."

To reveal the network, Aron and a team of researchers from UCLA, Oxford University and the University of Arizona performed two types of neuroimaging scans on healthy volunteers.

They used diffusion-weighted MRI, in 10 subjects, to demonstrate the "cables" between distant regions of the brain known to be important for control, and they used functional MRI, in 15 other subjects, to show that these same regions were activated when participants stopped their responses on a simple computerized "go-stop" task.

One of the connected regions was the subthalamic nucleus, within the deep-seated midbrain, which is an interface with the motor system and can be considered a ‘stop button’ or the brake itself. A second region was in the right inferior frontal cortex, a region near the temple, where the control signal to put on the brakes probably comes from.

"This begs the profound question," Aron said, "of where and how the decision to execute control arises."

While this remains a mystery, Aron noted that an additional, intriguing finding of the study was that the third connected node in the network was the presupplementary motor area, which is at the top of the head, near the front. Prior research has implicated this area in sequencing and imagining movements, as well as monitoring for changes in the environment that might conflict with intended actions.

The braking network for movements may also be important for the control of our thoughts and emotions.

There is some evidence for this, Aron said, in the example of Parkinson's patients. In the advanced stages of disease, people can be completely frozen in their movements, because, it seems, their subthalamic nucleus, or stop button, is always ‘on’. While electrode treatment of the area unfreezes the patients' motor system, it can also have the curious effect of disinhibiting them in other ways. In one case, an upstanding family man became manic and hypersexual, and suddenly began stealing money from his wife to pay for prostitutes.

Examples like these motivate Aron to investigate the generality of the braking mechanism.

"The study gives us new targets for studying how the brain relates to behavior, personality and genetics," Aron said. "Variability in the density and thickness of the 'cable' connections is probably influenced by genes, and it would be intriguing if these differences explained people's differing abilities not only to control the swing of a bat but also to control their temper."

More information is available from the University of California’s press release.

Labels:

Health,

News,

Psychology

Posted at

5:20 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Wednesday, 4 April 2007

Happy feet hit treadmills to track climate change

By Liz Tay

By Liz Tay

They may not be able to tap dance, but king penguins in the Antarctic could in fact have a role in monitoring the effects of climate change, new research suggests.

Scientists have long studied our changing environment in terms of unusual animal behaviour, such as altering patterns of fish and bird migration. Now, a research team from the University of Birmingham is finding out if the energy requirements of king penguins could be used as an alternative bio-indicator to monitor the health of the environment.

King penguins predominantly feed on a variety of fish called myctophid fish, explained bioscientist Lewis Halsey, who led the research on Possession Island in the South Indian Ocean. As the Southern Oceans warm, these fish tend to migrate further South, and away from the Islands inhabited by king penguins, he said, which makes hunting more difficult for the penguins.

“As the king penguins have to work harder to forage for the fish, their energy expenditure in doing so will increase,” Halsey said. “[This tells] us that the myctophid fish are changing location and becoming more sparse in areas of the Southern Oceans where king penguins forage.”

To ascertain the penguins’ energy requirements, researchers have implanted miniature heart rate data loggers into the birds. The penguins’ heart rates are then collaborated against energy expenditure under laboratory conditions, by getting the penguins to walk on a treadmill at different speeds. This data provides a correlation between heart rate and rate of energy expenditure, so any heart rate data subsequently obtained when the king penguins go to sea to forage can be used to estimate energy expenditure.

“We have deployed these loggers on birds for several years so we can look to see if the energy expended by king penguins from year to year is changing, which may give us information on the availability of myctophid fish in the Southern Oceans each year,” Halsey said.

More data is needed from the heart rate loggers during the next few years before any long term trends can be established. If the energy expended by king penguins at sea increases over time, it is likely that myctophid fish are getting harder to come by, which could be due to the warming of the Southern Oceans, Helsey said.

Labels:

Animals,

Environment,

Liz,

News

Posted at

11:59 am

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Tuesday, 3 April 2007

Hello, Hogwarts: invisibility cloak created

Researchers using nanotechnology have taken a step toward creating an ‘optical cloaking’ device that could render objects invisible by guiding light around anything placed inside the cloaked area.

Researchers using nanotechnology have taken a step toward creating an ‘optical cloaking’ device that could render objects invisible by guiding light around anything placed inside the cloaked area.

The theoretical design uses an array of tiny needles radiating outward from a central spoke. The design, which resembles a round hairbrush, would bend light around the object being cloaked.

Background objects would be visible but not the object surrounded by the cylindrical array of nano-needles, said Vladimir Shalaev, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Purdue University and one of the researchers developing the cloak.

The design does, however, have a major limitation: It works only for any single wavelength, and not for the entire frequency range of the visible spectrum, Shalaev said.

"But this is a first design step toward creating an optical cloaking device that might work for all wavelengths of visible light," he said.

Calculations indicate the device would make an object invisible in a wavelength of 632.8 nanometers, which corresponds to the colour red. The same design, however, could be used to create a cloak for any other single wavelength in the visible spectrum, Shalaev said, and could potentially cloak an area as large as a person or an aircraft.

"What we propose is the cloaking of objects of any shape and size," Shalaev said.

"If you satisfied only the first requirement of preventing light from reflecting off of the object, you would still see the dark shadowlike shape of the object, so you would know something was there," Shalaev said. "The most difficult requirement is to bend light around the cloaked object so that the background is visible but not the object being cloaked. The viewer would, in effect, be seeing around, or through, the object."

The device would be made of so-called ‘non-magnetic metamaterials’, which are synthetic materials that have no magnetic properties. Having no magnetic properties makes it much easier to cloak objects in the visible range but also causes a small amount of light to reflect off of the cloaked object, researchers say.

A key factor in the design is the ability to reduce the amount by which the material refracts light, so that its index of refraction is less than one. Refraction occurs as electromagnetic waves, including light, bend when passing from one material into another.

Natural materials typically have refractive indices greater than one. The new design reduces a refractive index to values gradually varying from zero at the inner surface of the cloak, to one at the outer surface of the cloak, which is required to guide light around the cloaked object.

Creating the tiny needles would require the same sort of equipment already used to fabricate nanotech devices. The needles in the theoretical design are about as wide as ten nanometers, or billionths of a meter, and as long as hundreds of nanometers. They would be arranged in layers emanating from a central spoke in a cylindrical shape.

Although the design would work only for one frequency, it still might have applications, such as producing a cloaking system to make soldiers invisible to night-vision goggles.

"Because night-imaging systems detect only a specific wavelength, you could, in theory, design something that cloaks in that narrow band of light," Shalaev said. Another possible application is to cloak objects from "laser designators" used by the military to illuminate a target, he said.

Researchers say that creating a cloak for rendering total invisibility in the entire visible spectrum would be a bigger challenge, requiring further advances in optical metamaterials and new combinations of nanotechnology with highly abstract ideas.

More information is available from Purdue University's press release.

Labels:

News,

Technology

Posted at

11:15 pm

|1 comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Monday, 2 April 2007

Male circumcision to control HIV infection

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, UNAIDS, have recommended that male circumcision be added to approved interventions to reduce the risk of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, UNAIDS, have recommended that male circumcision be added to approved interventions to reduce the risk of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men.

The recommendation follows what was found to be compelling evidence of the benefits of male circumcision, as presented by three trials carried out on African men between the ages of 18 and 24.

One study was held in Kisumu, Kenya where an estimated 26 percent of uncircumcised men are HIV infected by age 25. The majority of the 2,784 HIV negative, uncircumcised men who participated in the study were Luo, an ethnic group that does not traditionally practice circumcision.

Half the men were randomly assigned to circumcision and half the men remained uncircumcised for two years. Participants received free HIV testing and counselling, medical care, tests and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, condoms and behavioural risk counselling during periodic assessments throughout the study.

The clinical trial, which was led by Robert Bailey, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Illinois, found that 47 of the 1,391 uncircumcised men contracted HIV, compared to 22 of the 1,393 circumcised men.

"Our study shows that circumcised men had 53 percent fewer HIV infections than uncircumcised men," said Bailey. "We now have very concrete evidence that a relatively simple surgical procedure can have a very large impact on HIV."

Two other trials, held in Uganda and South Africa, yielded similar results, indicating that circumcision effectively reduced the rate of new HIV infections by 48 to 60 percent.

But experts warn that countries should consider male circumcision as part of a wider HIV prevention package, including HIV testing and counselling services to prevent men developing a false sense of security.

Circumcised men may feel they are protected from becoming HIV infected, Bailey said, and may be more likely to engage in risky behaviour. However, he said, ‘circumcision is by no means a natural condom’, concluding that circumcision will be most effective if it is integrated with other prevention and reproductive health services.

Kenya's director of Medical Services, James Nyikal, cautiously welcomed the recommendation from the WHO and UNAIDS.

"Although male circumcision considerably reduces the risk of HIV/AIDS transmission, there is a high risk of circumcised men becoming complacent and engaging in risky sexual behaviour," he said.

But while Kevin De Cock, director of HIV/AIDS at the WHO, acknowledges that it will be a number of years before the impact of the research is evident on the HIV epidemic, he said that the joint recommendations of the WHO and UNAIDS represent ‘a significant step forward in HIV prevention’.

"Countries with high rates of heterosexual HIV infection and low rates of male circumcision now have an additional intervention which can reduce the risk of HIV infection in heterosexual men," he said.

More information is available from the University of Illinois’ press release and from SciDev.net’s article announcing the WHO/UNAIDS recommendation.

Labels:

Health,

News

Posted at

11:20 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Friday, 30 March 2007

Genetically modified crops, ten years on

Is the expansion of genetically modified (GM) crops still seen as risky, or will it in fact help with the doubling of the food supply required as Earth’s population hits nine billion within the next 40 years?

Is the expansion of genetically modified (GM) crops still seen as risky, or will it in fact help with the doubling of the food supply required as Earth’s population hits nine billion within the next 40 years?

Ten years after the first GM crops were planted, evidence is mounting that the technology can increase crop yields with apparently little environmental impact, particularly in developing countries. In India, for example, GM cotton has increased yields by around 150 per cent, trebled small farmers’ profits, and reduced pesticide volumes by 80 per cent. In Australia, GM cotton has also significantly decreased pesticide use while raising farmers’ yields.

Anti-GM groups, however, argue that in many developing countries, GM crops are now grown mainly for export by big farmers, not for local consumption, and that there are big effects of this monoculture cropping.

Most Australian states, including Victoria and New South Wales, have imposed moratoria on GM crops until 2008. But according to a 2005 ABARE report, ongoing moratoria could result in Australia losing billions of dollars in foregone profits over the next decade, particularly as global warming impacts crop environments.

University of Melbourne agronomist Rob Norton claims that the vigorous seedling growth of hybrid GM canolas helps them compete against weeds and shortens the interval to harvest, reducing exposure to heat at the end of the growing season, and meaning less irrigation is required. This trait would allow canola plantings to be expanded into drier areas, potentially boosting annual Australian production of canola by 295,000 tonnes annually.

More information is available from CSIRO's press release

Labels:

Environment,

News

Posted at

5:11 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Thursday, 29 March 2007

Present day mammalian ancestors walked in the time of dinosaurs

Scientists have long thought that the mass extinction of the dinosaurs around 65 millions years ago opened the door for modern mammal species to proliferate. But a new, complete 'tree of life' tracing the history of all 4,500 mammals on Earth shows that they did not diversify as a result of the death of the dinosaurs, researchers claim.

Scientists have long thought that the mass extinction of the dinosaurs around 65 millions years ago opened the door for modern mammal species to proliferate. But a new, complete 'tree of life' tracing the history of all 4,500 mammals on Earth shows that they did not diversify as a result of the death of the dinosaurs, researchers claim.

The study, conducted by an international team of researchers from Munich, the U.S., the U.K. and Australia, contradicts the previously accepted theory that the Mass Extinction Event (MEE) that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago prompted the rapid rise of the mammals we see on the earth today.

“This is the first time such a large history of mammal evolution has been constructed,” said team member Marcel Cardillo, a visiting fellow at the School of Botany and Zoology at The Australian National University.

By comparing data from a range of sources including the fossil and molecular records, the researchers show that most existing mammal orders first appeared between 100 and 85 million years ago, well before the meteor impact that is thought to have killed the dinosaurs.

However, throughout the Cretaceous epoch, when dinosaurs walked the earth, these mammal species were relatively few in number, and were prevented from diversifying and evolving in ecosystems dominated by dinosaurs, scientists say.

The tree of life shows that after the MEE, certain mammals did experience a rapid period of diversification and evolution. However, most of these groups have since either died out completely, such as Andrewsarchus (an aggressive wolf-like cow), or declined in diversity, such as the group containing sloths and armadillos.

The researchers believe that our 'ancestors', and those of all other mammals on earth now, began to radiate around the time of a sudden increase in the temperature of the planet – ten million years after the death of the dinosaurs.

“Our study shows that modern mammal ancestors appeared millions of years before the dinosaurs disappeared, and then chugged along at low rates of species diversity for many more millions of years before exploding into the multitude of species we see today,” Cardillo said.

Cardillo said it would take many more years of study to find out the reasons why modern mammal ancestors were around for so long before they diversified, but suggested that it could be the result of complex relations between mammals and other animal species, and variations in the Earth’s climate, geology and atmosphere.

More information is available from the Australian National University’s press release.

Labels:

Ancient Worlds,

News

Posted at

10:31 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Wednesday, 28 March 2007

Cane toads invade new Australian terrain

By Liz Tay

By Liz Tay

As the nursery rhyme goes, there was an old lady who swallowed a fly. To catch the fly, she swallowed a spider. To catch the spider she swallowed a bird … and so on, until she died, of course.

Cane toads first reached Australian soil under similar premises. When they were introduced to the Northern Territory in 1935, they were expected to combat the cane beetle, which is a pest of sugar cane crops. While the toads did not alleviate the problem with beetles, they did quickly become accustomed to the Australian climate, and they bred fast. Farmers soon found themselves faced with larger, wartier pests than cane beetles – the cane toads themselves.

For the past 70 years, residents of Perth and Adelaide have watched cane toads spread from the Northern Territory through tropical Australia, and thought it had nothing much to do with them. But new research by an international team of scientists, including ecologist Rick Shine of the Sydney University’s School of Biological Science, claims otherwise.March of the toads

Previous predictions about the behaviour of cane toads, which go by the scientific name Bufo marinus, indicated that the species would be limited to tropical environments like those in Central and South America, from which the toads were originally imported.

Confounding these beliefs, the toads were now found to have adapted to dry conditions and temperatures ranging from 5 to 27 degrees Celsius.

“The toads have adapted rapidly to Australian conditions, and now tolerate much higher temperatures than was the case when they first arrived on our shores in 1935,” Shine said. “As a result, toads have managed to spread much further, into climatic zones also found widely through southern Australia – so there is no reason to think they will remain only in the tropics.”

Mathematical modelling by Shine and his team shows now predicts that toads will be able to live and breed in large areas of Western Australia, South Australia and western Victoria, and in several pockets along the New South Wales coast.

Current and projected range of invasive cane toads in Australia - Rick Shane et al

The researchers estimate the toads’ range to be about 1.2 million square kilometres across the Northern Territory and Queensland. This is a dramatic increase from estimates made by the same research team a little over a year ago, in which cane toads were thought to have spread to more than a million square kilometres in tropical and sub-tropical Australia.

Additionally, the rate at which cane toads are invading is not only fast – it’s also getting faster, researchers found. Compared with a rate of only 10 kilometres a year in the 1940s, the toads are now found to be advancing at more than 50 kilometres annually. Researchers speculate that this could be a result of evolution, as toads with longer legs were found to have an evolutionary advantage over shorter-legged counterparts.Beware warty hitch-hikers

Most of the potential range of the cane toad in southern Australia is separated from the toads’ tropical range by very large expanses of desert, which the researchers expect to be too dry for a toad to cross.

But although the toads may initially be deterred by these dry expanses, Shine said it is likely that the toads will cross such areas as hitch-hikers among rubbish or equipment in the back of a truck.

According to Shine, a nationwide invasion of cane toads is ‘inevitable’.

“[The arrival of cane toads] will probably depend upon fortuitous hitch-hiking events, rather than the toads dispersing all the way under their own steam,” he said. “The toads are superb invaders, and so far, none of the attempts to slow them down seem to have been very successful.”

Due to their toxicity and eating habits, the arrival of cane toads could spell bad news for some native fauna, pets and large predators. However, Shine expects most species to be relatively unaffected.

“Our work in the Northern Territory indicates that the toads dramatically affect only a few species,” he said, “[which are] mostly large predators like goannas, that try to eat the toads and are poisoned as a result.”

The spread of cane toads is expected to provide a good model system for understanding what invasive species will do in general, Shine said. Researchers are now expecting similar shifts in other invaders as well, as they adapt to the Australian climate.

Labels:

Animals,

Features,

Liz

Posted at

1:04 pm

|0

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Tuesday, 27 March 2007

Genetically modified pigs could yield organs for human bodies

By Liz Tay

By Liz Tay

Recent medical advances may shine new hope on the otherwise dismal shortage of human organ donors, by allowing the organs of animals to be transplanted into human bodies instead. It may be awhile yet before the technology, known as xenotransplantation, reaches medical clinics; but when that happens, accusing someone of being pigheaded may take on a new meaning altogether.

Xenotransplantation has been studied and attempted for over a century, but few operations have been successful to date. According to Muhammad Mohiuddin, who studies xenotransplantation at the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the major stumbling block of existing techniques is that the immune system in the animal receiving the organ tends to reject the transplant.

"We are still learning about new immunological hurdles and have to overcome these barriers in non-human transplant models," Mohiuddin said.

To study these immunological issues, scientists have studied xenotransplantation across several animal combinations, including the insertion of hamster organs into rats, and later into mice, as well as the transplantation of organs from pigs to baboons.

In a recent paper published in the esteemed journal PLoS Medicine, Mohiuddin cites a study in which insulin-producing cells, called islets, from pigs were transplanted into monkeys with diabetes. This led to the complete reversal of diabetes for over 100 days, researchers said.

However, suppressing immunological issues in the pig-to-monkey studies involved giving the monkeys drugs called immunosuppressants in doses that would be too large to be administered in humans. To overcome the need for overly large amounts of immunosuppressants, Mohiuddin suggests organs be farmed from pigs that are genetically modified to be more compatible with humans.

"Taking out some molecules which are immunogenic to humans and putting in human molecules [in the pig] will make the pig organ more compatible to humans," he said. "This allows us to use safer immunosuppression methods, which are now routinely used in allotransplantation [organ transplantation from human to human]."

Pigs were chosen as potential donors for their organ size, which is said to be comparable to human organs, their short breeding cycle and large litter size, and our ability to genetically manipulate their immune system, Mohiuddin explained.

While there are still some hurdles between current research and the potential use of pigs in human organ donation, such as the objections of animal rights proponents and concerns to do with the transmission of viruses across species, Mohiuddin believes there is a strong case for further research into xenotransplantation.

"In [the] United States alone there are more than 90,000 patients waiting for organ transplantation and only 25,000 transplants were performed during last year," he said. "Most of these patients will die waiting for the organs."

"Xenotransplantation has the potential to save many lives," he said.

Labels:

Animals,

Health,

Liz,

News

Posted at

11:49 pm

|2

comments

|

E-mail to a friend

| DiggIt! |

Del.icio.us

![]()

Monday, 26 March 2007

Subconcious tactics of penalty box soccer

By Reidar von Hirsch

By Reidar von Hirsch

Scientists at Hong Kong University have come up with a theory that might prove extremely useful for football players around the world. Had Mark Schwarzer known in the fateful World Cup match against Italy last year what these Hong Kong scientists know today, Australian soccer fans might still be cheering.